Public Works and Infrastructure in Ancient Rome

When reviewing the great public works of ancient Rome, three things come to mind: aqueducts, public baths, and the Cloaca Maxima.

One of the essential attributes of any great city is a constant supply of fresh, clean water. In the ancient world clean water was a rare commodity. The city of Rome sits beside the Tiber River, but two thousand or more years ago there was no way to reclaim enough clean potable water from that river to supply a fast growing city that continued to dump its waste into the same river. The city's water supply depended on local wells, often privately owned, and rain water that was collected in cisterns. This served the city's needs for a time, but it hindered Rome's growth and prosperity. It was after the last king of Rome was deposed and the Republic began to flourish that there was both a greater need and the greater ability to solve the water problem.

Two innovations made aqueducts possible. The first was the arch which was adopted from the Etruscans, and the invention of concrete. Roman concrete was made of hydrate lime mixed with small rocks and volcanic ash. These simple ingredients made structures that have lasted thousands of year. Between 312 BC and the end of the Roman republic, eleven aqueducts would be built to meet Rome’s ever growing need for fresh water. Hundreds of other aqueducts were built throughout the empire.

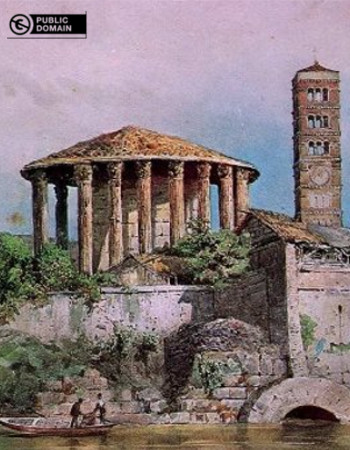

To bring fresh water into the city, the Romans did not look to the river, but rather to the freshwater springs in the hills around the city. In 312 BC, Appius Claudius Caecus commissioned the building of the city'’'s first aqueduct. The Aqua Appia flowed just over ten miles to enter the city from the east and terminate at the Forum Boarium near the Tiber River. Most of this aqueduct was underground because it was flowing from a nearby spring at the proper height. It was important that the aqueduct was not too exposed, as Rome was at war with her Samnite neighbors and an exposed aquaduct would be an easy target.

Most of the many miles of aqueducts were underground. Less than 5% of all Roman aqueducts run above ground, but it is the grand arches spanning valleys and crossing rivers that excites our imaginations. Most of the underground channels were cut through the hillside creating a trench from a nearby water source. The cut trench was lined with concrete, capped with stones or vaults, and covered. The gradient along which the water flowed needed to be carefully calculated to prevent the water from either rushing too fast through the pipes and causing damage or moving too sluggishly and becoming stagnant.

Once arriving in the city, the water from the aqueducts needed some place to go. Much of the water was diverted to public fountains to meet the drinking and cooking water needs of the city's citizens, but a good deal of the water was diverted to public baths. The public baths or thermae were places used for both cleaning of the body and for recreation. The public baths were places where people could meet and socialize, buy cooked food, listen to music, exercise, and relax. Mst major Roman cities had at least one baths and Rome had several large and numerous minor baths, including some in private homes.

A public bath was built around three main rooms. There was the frigidarium which was a cold bath. There was also the tepidarium, or warm bath, and finally there was the caldarium, the hot bath. Some of the thermae as the baths are called in Latin had steam baths and sauna like rooms.

Larger thermae were laid out with separate facilities for men and women, but some smaller baths segregated the times the genders could use the facilities. Larger baths also featured an open exercise area, latrines, and stalls for serving food. Some baths even provided entertainment.

Since soap was a scarce luxury item and unavailable in most parts of the world, bathers were cleaned by being first rubbed down with oil. As the oil absorbed the dirt from the skin, a slave would use a strigil, a curved scraper to remove the oil. The bather would then enter the water for a relaxing rinse or soak.

After leaving the fountains, washbasins, and baths, the dirty water needed to go somewhere. Where it went was to the Cloaca Maxima, the great sewer of Rome. This great sewer began its time as a humble trench built around 500 BC to drain the marsh that filled the area between the hills of Rome that became the Forum Romanum. The sewer was named for the goddess Cloacina who presided over sewers, drains, and oddly enough, sexual intercourse.

After the trench was enclosed and the forum was built over it, it became a great sewer that extended through the forum and into the subura, the low area of the city between the great hills. The other end of the sewer drained into the Tiber River as it still does today.

The Cloaca Maxima ranges in size from 5' x 5' to 11' x 12' and is constructed of stone and concrete. In the city of Rome many of the paved streets had drain holes that emptied into the great underground passage as did the numerous public latrines that dotted the city With water flowing from pipes branching off from the aqueducts under the seats in the latrines and out to the Tiber River.

These links are being provided as a convenience and for informational purposes only; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by Nomenclator Books or Bill O'Malley of any of the products, services or opinions of the corporation or organization or individual. Nomenclator Books and Bill O'Malley bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.