Politics in the Time of Caesar

In theory, there was a part to be played in Roman political life by every free adult male. In reality, the class structure of Roman society gave more political power to the senatorial class and particularly the patricians. As did many aspects of Roman society, politics evolved over time, but for now we will focus on politics as it was practiced approaching the end of the republic.

While it is tempting to think in terms of political parties, Roman politics was dominated by two factions. However, the political goals of the major players was nearly always personal advancement of themselves or their families. The upper classes generally followed one of two informal political factions. /

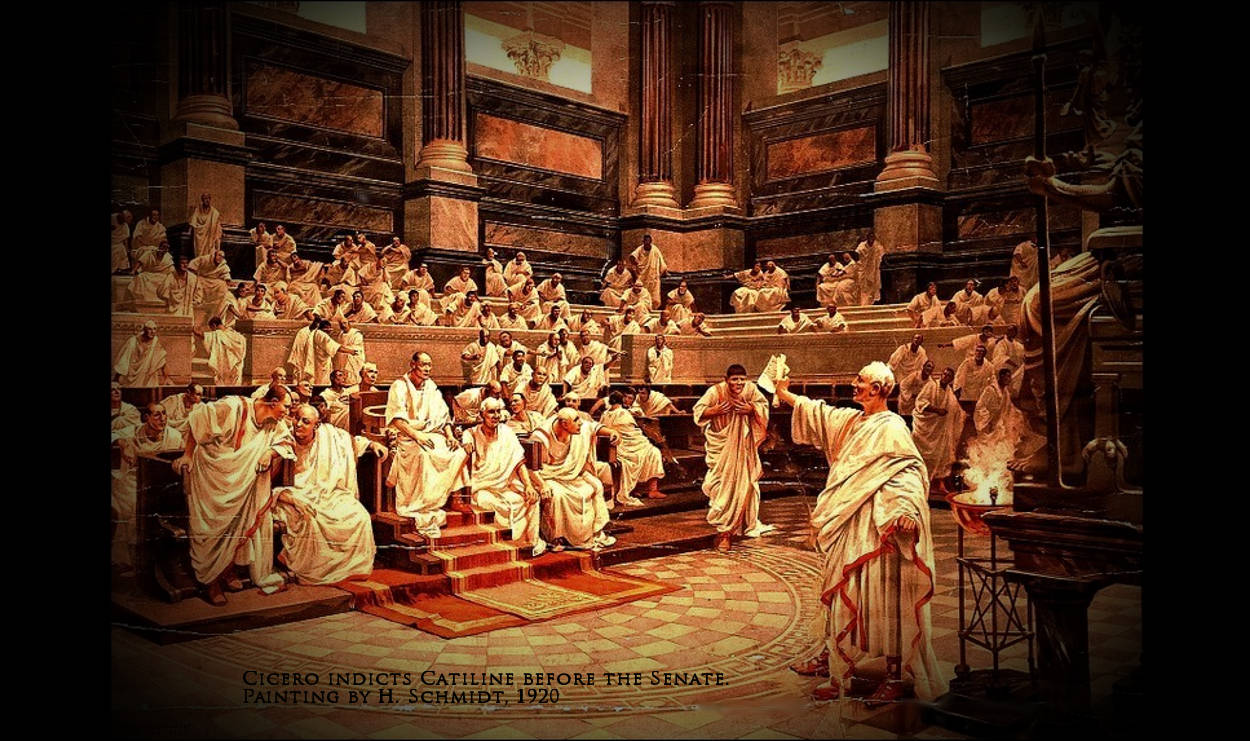

There were the Populares, representing the common people, and the Optimates, representing the “best men.” The power base of the Populare faction was the Assembly of the Tribes and the tribunes. Though also composed of Senators and nobles, this faction appealed to the interests of the plebeians, or common people. On the other hand, the Optimates had as their power base the Senate. This faction promoted conservative policies that supported the interests of the wealthy and the old noble families.

Sallust, writing in the mid first century BC described the conflict between the two factions:

After the restoration of the power of the tribunes in the consulship of Pompey and Crassus, this very important office was obtained by certain men whose youth intensified their natural aggressiveness. These tribunes began to rouse the mob by inveighing against the Senate, and then inflamed popular passion still further by handing out bribes and promises, whereby they won renown and influence for themselves. They were strenuously opposed by most of the nobility, who posed as defenders of the Senate but were really concerned to maintain their own privileged position. The whole truth—to put it in a word—is that although all disturbers of the peace in this period put forward specious pretexts, claiming either to be protecting the rights of the people or to be strengthening the authority of the Senate, this was mere presence: in reality, every one of them was fighting for his personal aggrandizement. Lacking all self-restraint, they stuck at nothing to gain their ends, and both sides made ruthless use of any successes they won. (Sallust Bellum Catilinae 38, translated by S. A. Handford [Penguin Classics, 1963], 204-205)

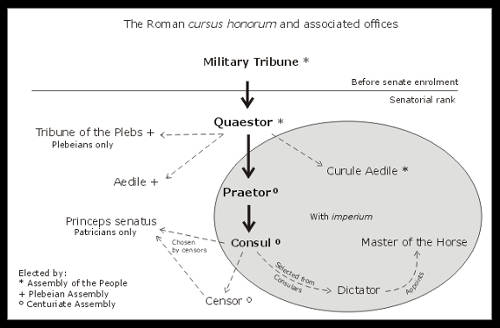

The achievement of political office was a mark of honor in Roman society, and to achieve the highest honor, the office of the Consulship, was the pinnacle of a man’s career. Many attempted to reach that goal, but few made it as there were only two elected each year, and some men were able to get elected more than once. To rise to the consulship reflected on the honor of a man’s family for many generations.

In Roman society there was a longstanding relationship between men of society. There were political, social, familial, and even tribal bonds that led to system of patronage that spanned the length and breadth of society. A man’s clientela was essential to his political success and clients were expected to support and vote for their patrons. As a result, prominent Romans worked to maintain solid relationships with their existing clientela and to, if possible, expand their base.

When a man campaigned for office, setting out in the artificially whitened toga candida, he needed to spend a great deal of money to ensure success. Elections were as much about personalities as they were about issues and a successful politician needed to feed and entertain the electorate. Fortunes were borrowed and spent in trying to achieve office. One of the best ways to impress the electorate was to stage extravagant games during religious festivals. These games involved staged gladiatorial combats and wild beast hunts, chariot races, and elaborate feasts for thousands of citizens. It was illegal for a candidate to directly pay for a banquet for the voters, so this was done through intermediaries. However, it was expected that office holders on the lowers of the Cursus Honorum, or “course of honor,” the ladder of political offices leading to the consulship, stage games during the many religious festivals. Should an Aedile be planning to run for the Praetorship, he would make sure the voters would remember the games he staged. This sort of campaigning was tremendously expensive.

In the time represented in the Nomenclator series, bribery was a necessity for political success, so in addition to providing entertainments and banquets, money was often given directly to voters.

Since there were no salaries paid to politicians, the money spent in getting elected needed to be recouped. This was often done, at least in the last century of the republic, but attaining a posting to a province. Being sent to govern a province, ruling with a great deal of independence and very little oversight, allowed a man to collect a great deal of money through business opportunities and corruption.

In addition to gaining the support of the common people it was also important to have the support of other powerful families, especially of the patrician class. The leading men of these families could direct their vast clientela as to how to vote on election-day. These alliances were often solidified through marriages and adoptions.

As the elections near the end of the republic became more chaotic and the factions more polarized, office seekers began to turn to intimidation and violence.

In theory, all adult male Roman citizens were able to participate in elections for candidates and for or against proposed legislation. For this purpose there were two assemblies, the Assembly of the Centuries and the Assembly of the Tribes, depending on whether the election was to decide on a candidate or a proposed law, or possibly a priesthood or special office. Voting was done in groups of either Centuries or Tribes. Each voter was given a small piece of wax covered wood on which he would mark his choice. The tablet was then dropped into a large urn. This voting needed to be completed in a single day, so as many voters as possible assembled in the open space on the Campus Martius.

While the Roman republic represented a huge step forward in popular representation, it was seriously flawed. Women had no political role unless it was to influence their male relatives. Also, the vote was unequally weighted in many elections with a greater weight given to the votes of the upper-class. In the end the system was not up to the task of electing officials who would run a vast empire. Great distances and slow communication led to little oversight of those who governed distant lands leading to the sort of corruption that could amass great wealth. That wealth tempted men to achieve the highest offices not just for honor or out of a sense of civic duty, but to get posted to a province where they could amass fortunes. Eventually the Roman Republic collapsed to be replaced by the Principate.

These links are being provided as a convenience and for informational purposes only; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by Nomenclator Books or Bill O'Malley of any of the products, services or opinions of the corporation or organization or individual. Nomenclator Books and Bill O'Malley bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.