Ancient Roman Medicine

Ancient Roman medicine was a combination of superstition, religion, folk wisdom, and some genuine medical knowledge gained through trial and error and contact with other cultures, most notably, Greek. Roman medicine relied heavily on Greek physicians and their knowledge, but traditionalists, such as Pliny the Elder and Cato advocated traditional Roman healing practices. These involved a good deal of superstition, including prayers, chants, charms, and magical practices. There was an herbal component to traditional Roman healing that may have provided more practical relief. The concept of contagion was understood, if vaguely, prompting physicians to isolate sick people, but often a divine or malevolent force was thought to be involved, so a variety of rites went hand in hand with medical treatment and attempts at sanitation. Diet and herbal medicines were also frequently prescribed to treat and prevent diseases.

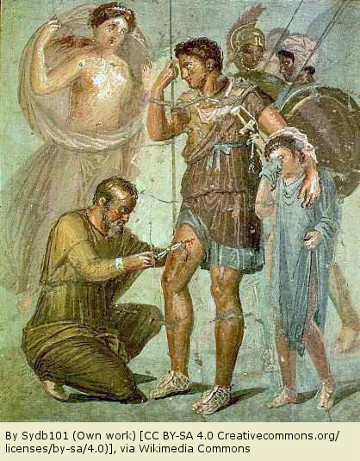

Roman tradition held that, Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine arrived in Rome in 291 BC. The legend states that when plague struck Rome in 293 BC, Roman priests consulted the Sibylline Books for assistance. Based on their interpretation of the texts, a delegation was sent to visit the sanctuary dedicated to Asclepius in Epidaurus, Greece and return with a statue of the god. During the propitiatory rites, a large snake slithered from the temple and onto the Roman ship. As the snake was one of the god’s attributes, the Romans took this as a good sign. As the returning ship sailed up the Tiber River and approached the city, the snake slithered ashore onto an island in the river. The Romans took this as a sign that they were to build a temple to the god on the island. The temple was dedicated in 289 BC and the plague ended. To this day, a hospital stands on the site at the east end of Tiber Island. After Rome assumed rule over the Greek peninsula in 146 BC, the influence of Greek medical practice on Roman society became even greater. From the Greek physicians, Romans adopted various techniques, including a variety of surgeries, as well as greater knowledge of the use of herbal cures and treatments.

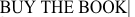

The warlike nature of the Romans also led to many medical advances. Every Roman caster, or fort had a valetudinarium, a sort of hospital. If it was a marching fort it was a housed in a cluster of tents, but if it was a more permanent fort, the hospital was a well-planned structure. The necessities of war forced the practitioners who traveled with the army to develop new techniques for treating wounds and diseases. If one were to compare an ancient Roman set of surgical tools to one from the nineteenth century, they would be surprisingly similar, demonstrating a solid understanding of surgery. Civilian hospitals were not know until at least the first century AD, well after the time in which the Nomenclator series is set.

Archaeologists have identified a variety of surgical instruments, including:

Scalpels of either steel or bronze.

Forceps for grasping small objects difficult to reach with the fingers.

Uvula forceps. These forceps had toothed jaws, used in amputating the uvula.

Bone Drills, used to bore holes in the skull or to remove foreign objects from bones.

Surgical saw for cutting through bones in amputations.

Hooks. Hooks could be either sharp or blunt depending on their purpose.

Catheters of steel or bronze used to open a blocked urinary tract. Straight catheters were used to treat men while catheters with a slight curve were used for women.

Vaginal specula, similar to those used up until the nineteenth century.

Spatula for applying ointments and slaves.

While medical practice in ancient Rome was nowhere near what is available to the modern world, it was, in many respects, far superior to what was practiced during the dark ages that followed the fall of Rome. The level of treatment and care would not be equaled again for several centuries.

These links are being provided as a convenience and for informational purposes only; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by Nomenclator Books or Bill O'Malley of any of the products, services or opinions of the corporation or organization or individual. Nomenclator Books and Bill O'Malley bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.