Castrum is the Latin word for a fortification. From that the modern word “castle” is derived and, in Britain, place names for towns that were once Roman forts. The suffix “caster” and “chester” in city names such as Lancaster and Colchester are reminders of the forts they once were.

There were four types of Roman fortifications. The castra stativa were permanent fortresses used to station garrison forces in occupied territory. The castra aestiva were summer camps or fortresses used for forces in the field. Castra hiberna were winter fortresses occupied by troops holding territory gained in summer campaigns, and castra navalia or castra nautica were navy camps or fortresses used to house soldiers in preparation for naval campaigns.

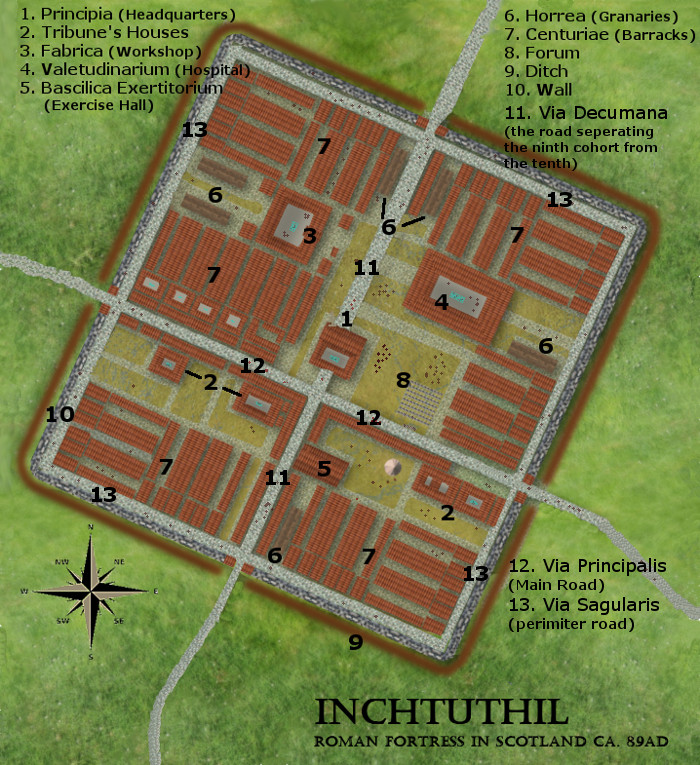

The castrum housed the soldiers, their equipment, their horses, and their supplies when they were not actively engaged or on the march. But with time, the castrum became much more. Originally they were little more than marching camps where the soldiers would retire after a long march, but over time the castrum evolved into permanent fortresses with hospitals stables, granaries, paved roads, and even manufacturing facilities. The use of a castrum as a manufacturing site was clearly demonstrated during the excavation of Inchtuthil, a Roman fortress discovered on the River Tay in Scotland. During the archaeological investigation of this first century AD fortress, a cache of over 750,000 iron nails was discovered. When the legion occupying Inchtuthil was recalled to the continent by the emperor, the soldiers buried the nails and razed and burned all the structures in the fortress, using the debris to conceal the pits. They almost certainly did so to deprive the enemy of the iron which could easily be turned into weapons. The horde of nails was so great that many of the nails were donated to museums or sold to raise money to pay for further excavation. What wasn’t sold or given away was later recycled. The image below is a representation of the layout of Inchtuthil with the principal features marked. This layout was typical of most Roman castra.

Most of the castra that were constructed shared the same basic layout as Inchtuthil but were only temporary fortifications to protect the legions on the march. Near the end of a day’s march, scouts and engineering units would locate a place to build the fort and the work would begin. Every castrum was constructed on level ground with a source of water, using the same layout each time, to ensure that every man would know his place in the event of an attack. The architecti, or chief engineers would use the men of their specialized unit to survey and lay out the camp which was to be constructed by the soldiers near the front of the line. For a legion marching to war or following an enemy, a new fortress was constructed near the end of each day in just a few hours and abandoned the following morning.

More permanent castra were built by carpenters and masons and were often better constructed than the local villages. When these fortresses were eventually abandoned by the legions, local people would move into them and they often became the foundations for future cities.

These links are being provided as a convenience and for informational purposes only; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by Nomenclator Books or Bill O'Malley of any of the products, services or opinions of the corporation or organization or individual. Nomenclator Books and Bill O'Malley bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.